|

| Arthur Shilling's self-portrait as seen at the Thunder Bay Art Gallery |

Many renowned commercial

art galleries in Canada represent Arthur Shilling’s work, with price estimates

at a few thousand for each painting, prices not unusual for a living Canadian

artist showing in a contemporary gallery. Shilling’s work is therefore greatly

undervalued, easily worth many times its current value, which should be up

there with the likes of David Milne.

Ojibway artist, Arthur

Shilling, was a great portraitist who played with a number of styles and

treated his subjects, mostly of Anishnaabe decent, with heartfelt reflection, revealing

his subject’s individuality and their connection to their community. His bold

expressionist use of line and paint are immediately awe-inspiring. The grand sizes

of some of his paintings help in this regard, but it is the unrestrained power

of his works that will grip you immediately.

The Thunder Bay

Art Gallery is currently hosting a show organized and circulated by the Art

Gallery of Peterborough till September 25. Titled Arthur Shilling: The Final

Works, the show covers a ten-year period between 1976 and 1986 when Shilling’s

boldness of style truly became identifiable. Many of the works in this show are

on display for the first time, garnered from private collections. One of the

most outstanding paintings is a nine meter long painting titled, “The Beauty of

My People.”

Sadly, as

reported by the Huffington Post in June, “a Mainstreet Research poll found that

54% of adult Canadians cannot name a single Canadian visual artist, living or

dead.” The author of the article, Grant Gordon, posits a few good reasons why

this is so, but misses what could be the prime reason for this problem.

In this show of

Shilling’s work you can see the quality and dedication he has for his own

people and for general humanist concerns. Shilling boldly and beautifully

expresses himself with great spontaneity and imaginative gusto while allowing

us to connect with the very real people that he painted from life. Very few

artists can master his skills and the added value of his work comes from his

being a fighter and a rebel for a great cause at which he is successful; bringing

dignity and beauty and awareness to a people that our Western forefathers

intended to extinguish.

That Shilling is undervalued is a sad

statement in itself. In comparison there has been a major effort for many years

to make David Milne Canada’s greatest artist. I don’t intend to be mean by

picking on Milne’s work so much, but he is the best representative of a major

problem we have in Canada and a reason why many Canadians can’t name a single

Canadian visual artist.

Milne’s works are somber landscapes of trees,

trees and more trees, featured in thousands of little paintings, each worth

many thousands and even hundreds of thousands of dollars. Yet limited talent is

required to produce these works, especially in comparison to that of

Shilling’s. Over the years I’ve met art connoisseurs, heard talks and watched

documentaries about Milne all making the claim that Milne is an underrated

Canadian artist who should be known to all as one of our greatest artists if

not our greatest.

Despite all the

talk I never bought into it. I was never moved by Milne’s late 19th

century and early 20th Century work, which I first saw at an early

age of fourteen when at the National Gallery in Ottawa. At the time I thought

he painted at a high school level. To me the land and trees in Milne’s works

were used primarily as a means to an end, the end being aesthetic experimentation,

a dedication to style above all else no matter what the subject matter. This is

most obvious in Milne’s war art. Where there could and should be statements of

human tragedy Milne’s works reveal a distinct lack of humanism. There is no

sympathy, empathy, heart or reflection. Soldiers and guns, fields of debris and

bomb craters are all painted as if people didn’t matter.

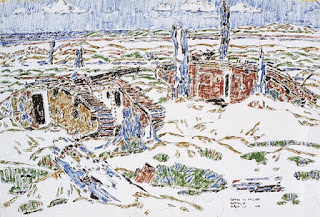

|

| Wrecked Tanks Near Sanctuary Wood by David Milne |

Milne’s focus was

with shape and form and colour scratching, which says nothing about the victims

of unparalleled violence. His paintings of war look rather peaceful in

comparison to any photograph or any other artist’s work. It even takes the

viewer a few moments to see the intended subject matter. The paintings are not totally

without merit, but they are lacking in the most basic functions of what art can

do with such dramatic subject matter.

For thousands of

years the hierarchical value attached to art started at the top with the

subject being humans in conflict, battles that were physical or intellectual or

religious where the victors could claim authority. This was High Art and it

included humans at the top, with portraiture above landscapes and landscapes

above animals and children.

Fine Art, which

existed in spurts throughout history until the present day, were experimental

and/or entertaining excursions only witnessed by the wealthy which did not

influence the popular arts celebrated by both wealthy and common people. High

Art influenced the popular arts throughout history, until the present day. High

Art exists in popular art, in spurts, but no longer in major institutions or

contemporary galleries. Popular Art today influences Fine Art, but Fine Art

rules the day in an intellectual’s mind and for anyone recording art history.

|

| A better than usual landscape painting by David Milne |

For example: the

federal government, at the turn of this century spent a million dollars to

properly document, collect and promote Milne like no other artist before him. A

grand show of his work crossed the country with pomp and ceremony. In 2012

another million dollars was spent for the David Milne Study Centre at the Art

Gallery of Ontario in Toronto.

Despite the

attempt to make David Milne a household name the public continues to expurgate

their confusion (a confusion brought on by the effort of having to compare the

big claims of value with the obvious inadequacy of the art), by opening their

mouths wide and letting out a big collective Canadian yawn.

Likely you have

no idea who David Milne is. Milne is an example of a Canadian artist firmly ensconced

in the world of the gallery system, supported and loved by those in the know

(and especially his collectors who have a vested interest in keeping their

stock of Milne’s work highly valued), but to whom the public finds next to

impossible to feel connected.

|

| A typical landscape by David Milne |

David Milne’s little

exercises in aesthetic quiet and stillness are a cold celebration of a land

without people. In this respect his work is similar to the more dynamic works

of the Group of Seven, whose works command even higher sales figures, yet also reveal

a great and sad neglect that is distinctly North American and continues to go

largely unacknowledged.

These landscape

painters are firmly ingrained to the settler’s myth of the Canadian experience,

a Conservative Harperist view of the land, an “Old stock Canadians” understanding

that Canada is a land free and unsoiled, always ready for exploration and

exploitation by anyone with enough motivation. Sadly, this ideal completely

ignores the existence of First Nations people who have lived on this land for

thousands of years before Western settlers arrived.

Emily Carr,

unlike her male Group of Seven counterparts is a great exception to the rule.

She acknowledged First Nations people in her work whereas David Milne is a

perfect example of an artist wholly uninterested in the people who lived on the

land. His work reflects, by neglect, an adherence to the myth of the land as a

rugged and free space.

The Huffington

Post article most notably ignores the fact that visual art can exist quite well

without sitting quietly in a gallery. The author suggests that art step out

from the gallery from time to time. This comment indicates that the author is biased

against popular art, an art form never requiring a gallery in order for the

work to be accepted by the larger public. Popular Art is humanistic in nature. Technological advances allowed Popular Art to morph from illustration, cartoons, painting and

sculpture into photography, television and movies. Meanwhile a desire to be

better and different from the masses has forced cultural elites to value

something the public sees little value in celebrating.

The overused

example of the Emperor’s New Clothes can be brought to this argument, but a darker

element at play is the negation of human values art is capable of expressing in favour of a history

of aesthetics where a minimalist anti-humanist purity has an almost

authoritarian resolve to ignore what popular art so brilliant offers and which

the public loves. By furthering the divide Canada’s cultural elite is inadvertently

creating the kind of division we see in England with its notorious

anti-democratic class system; a class divide that resulted in Brexit where the

disadvantaged lower classes, kept down and ignorant for centuries (which the EU

tried desperately and quietly to help) had an opportunity to go tribal and lash

out against the English upper class. This could likely end in England being ripped out of the European

Union.

Ford Nation in

Canada represents a similar growing divide and friction with Toronto’s cultural

elite out of touch with the average Canadian. Aiding in that process is an art

forced upon us rather than celebrated. It is they, the wealthy, who can collect

valuable works of art that are in fashion while the rest of us gaze at coffee

table books. And it is mostly they who claim to see the value in David Milne’s

work where most of the rest of us cannot.

|

| A screen shot on Google's Image Page for Arthur Shilling |

Art can at its

best can delve into who we are in our own time and when we do this honestly, representing

everyone, we leave a history of art that reveals who we are to future

generations. Anything else is a fog. If criticism in the arts is dedicated to

appeasing a cultural elite we will continue to undervalue great artists in our midst

who could do wonders for celebrating diversity and help create a peaceful

world, a world where artists like Arthur Shilling can receive as much attention

and be valued as much or more than an artist like David Milne. And I’m not

talking about money.

We have to

understand that in our time art historians and critics and artists themselves

have so refined their understanding of what art is that the entire history of

art can be changed with one word. What if art is not the history of aesthetics,

but a moral history? Every painting ever created in this country suddenly gets

valued differently. Or change the word to beauty or humanism or democracy or diversity

or… you see the point? Art is not any one thing and to make it so, to put the

emphasis so heavily on one word, destroys the value of art.

At the age of

twelve I was an enthusiastic visitor to the Thunder Bay Art Gallery, attending

openings and dropping in often for a second look to check out a show, biking all

the way across town. Since the age of twelve I was a great admirer of Rembrandt

Van Rijn’s classic paintings. Three months ago at the Hermitage in St.

Petersburg I was fortunate enough to lay my eyes on a few more original

painting by Rembrandt, some of his best. It was a thrill, but not like it used

to be when I was a young adult.

In comparison, I

remember the time when I first laid eyes on Arthur Shilling’s work in the 1980s

at the Thunder Bay Art Gallery. I was immediately inspired. I recognized

Rembrandt in Shilling’s work. I even tried my hand at copying Shilling’s style

and I’ve never forgotten Shilling’s name. A promotional card featuring a

Shilling self-portrait was nearly always within eyeshot, taped to the side of a

bookcase. I’ve always had his imagery in my head, and that of First Nations

people, painted as glorious, strong and vibrant individuals sometimes within a

swirling world of creatures, myths, and nature surrounding them. That

impression on my young mind had value, not only as an artist, but also as a person.

Drawn to an expressionistic style of

painting made popular before the 1950s Shilling adopted a natural drawing style

and spontaneous approach to painting which suited his talents. His style and

subject matter was a perfect rebirth and statement as to the value of an art

where people are more important to an artist than artistic ideology or the

whims of fashion in the art world.

Clement

Greenburg, an American Art critic who made Jackson Pollack famous, practically overnight,

anointed David Milne a great Canadian artist back in the 1950s. Greenburg also

anointed Canadian Jack Bush, an abstract artist, equally celebrated at the Art

Gallery of Ontario.

Greenburg is also

famous for destroying the Expressionist movement that existed before World War

II. He wrote extensively about the value of modernism over the moribund art of

the past and the popular arts. There’s no direct evidence, but Greenburg came

along at exactly the time when the CIA launched propaganda campaigns against

the Soviet Union, funneling millions of dollars into literary magazines, art

shows, and public performances in Europe and around the world to convince

Europeans and others that the United States was far more progressive and

accepting of modernism than the USSR. The Soviets made a huge mistake, unlike

modern China, in rejecting modern art. They murdered and cast out their

artists, which helped to convince Europeans that communism was a dangerous

ideology.

However, CIA

agents admitted back in the 1970s that the most successful campaign that convinced

Europeans of the American elite’s cultural acumen were the touring modern art

shows, shows that featured Jackson Pollock and the like. Fashion in art changed

quickly around the world in the 1950s, and all the progressive Expressionist

artists, black, white, women and men, gay and straight, vanished due to

complete lack of support. With the Guggenheims and the Rockefellers funneling

millions of CIA dollars through their institutions the art world was changed

forever and for the worse, to the point where no art historian dares mention

this alternate, factual and well-researched account of art history.

These huge

influences are with us today and continue to influence how we value art and

artists. The undervaluing of Shilling’s work and overvaluing of Milne’s and

Jack Bush’s and hundreds of others is a result of mass influences totally

unrelated to the human heart and unrelated to our needs. It is weakening the

best of what art has to offer and diminishing the ability of artists to change

the world to better the world for all of us.